If you think of the land as a palimpsest—a piece of fabric or hide, sturdy pergamena or velum, here wrinkled, here smooth—on which human and natural history is written and rewritten, then what are fires? Are they a kind of malevolent scribe, a wild artist flamboyant and expert in the colors of red and orange, then, finally, of gray and black, set loose by carelessness or coming full force apparently out of nowhere? Or are they the whitewashers, the blackwashers, the diligent scrapers that wipe clean or repaint the surface for it to be used again?

If you think of the land as a palimpsest—a piece of fabric or hide, sturdy pergamena or velum, here wrinkled, here smooth—on which human and natural history is written and rewritten, then what are fires? Are they a kind of malevolent scribe, a wild artist flamboyant and expert in the colors of red and orange, then, finally, of gray and black, set loose by carelessness or coming full force apparently out of nowhere? Or are they the whitewashers, the blackwashers, the diligent scrapers that wipe clean or repaint the surface for it to be used again?

There are six entries for “fire” in LeRoy Makepeace’s 1941 Sherman Thacher and His School, a chronicle of the first fifty years of Casa de Piedra—as many as for “Eliza Blake” (Mrs. Thacher), only one fewer than for “Morgan Barnes” (the teacher, the trail) and “Oranges,” but a whopping fourteen fewer than for “Yale.” Which might lead one to believe that fire played a dramatically less important role than did the on-going relationship between SDT and the home of the Elis.

Not true: Mr. Thacher’s first attempt, shortly after his arrival in the Ojai Valley, at a controlled burn of the brush-pile he and others had cleared from five acres of soon-to-be-planted olive orchard was a near disaster and what Makepeace calls “that sin which is greatest of all in a dry climate.” Lesson learned on set fires. But on June 17, 1895, with Mrs. Thacher and the boys mostly packed for summer break, and several of the latter sleeping on the piazza (a veranda off the present Hills Building), with a “gentle east wind blowing,” he and the School, while sinless, would not be so lucky. “When [Mr. Thacher] went to bed life seemed remarkably simple. Starting with little money and no experience he had founded a unique school. Admittedly the equipment was little better than adequate and the buildings were neither handsome nor luxurious. But he knew that the physical plant of a school is of slight importance to anyone except parents [!].”

Mr. Thacher woke to the boys’ alarmed yelling: a fire had started in the kitchen, and, wholly lacking adequate water with which to douse the sudden conflagration—no storage tanks, no reservoir, only a “thin dribble out of the pipe from Chicken Coop Canyon”—they could do nothing but work to get everyone out of harm’s way. Although “the boys saved a good many of their possessions… Mr. Thacher was able to rescue nothing but his desk and papers. Twenty-five minutes was the span from start to ruin. The newspaper reported the following day, “Casa de Piedra [the ranch] and the settlement of buildings that marked the location of Mr. Thacher’s Ranch School are in ashes except the barn, the sentinel-like chimneys and the blackened stone walls of the school building which gave the place its name.”

Yet—and this is the observation of character that sets me on my heels in admiration—despite losing virtually everything to the flames, with only $4,000 in insurance, and no bank account anywhere,” he remained calm during the tragedy, directing others with assurance. He arranged for everyone to spend the rest of the night at the Pierpont Cottages [down Thacher Road], and the next day he took the boys to Santa Barbara to catch the San Francisco boat [so as to take their Yale entrance exams].” Students and faculty first, and though there is no mention of horses, I’ll presume they made it to safety. And, standing in the ashes, Mr. Thacher announced that he would rebuild at once in the Ojai.

I wonder at this bold temerity, this resilience and grit. (Take that for a 19th century e.g., Angela Duckworth!) And his preternatural equanimity: Mr. Thacher’s late-July letter to his dear Yale friend Horace Taft (who’d founded his own school in Watertown, Connecticut, a year after SDT had scraped together his), written after the fire had taken down nearly all he had built, is laced with a surprising objectivity, even good humor, given the circumstances. While the fire was raging, I thought of you and wondered if this meant that we should get together after all and how nice it would be… I know you would welcome me and it would be delightful but I care a good deal about this life and the independence of the whole situation. Besides, I am not a very good teacher anyhow, and I don’t know how you could use me. My genius, as far as it goes, lies in managing boys and teaching a little here and there.

But there’s more. Among the outright cash gifts and pledges of help from family, friends, and mere acquaintances was this: the offer of “a fine tract of land in Santa Barbara” on which to reiterate his school. Reliable water, salutary climate year-round, scenic beauty, the Pacific at his feet.

Mr. Thacher declined; the home and school he’d made and had taken away would be made again, right where it started, thank you very kindly. To Horace: It seems best to stay here. (Fifteen years later, Curtis Cate, a one-year Thacher faculty member, would situate his school a little south of Santa Barbara—and 107 years after that, it would shelter in the gym about 300 Thacher students and faculty fleeing the Thomas Fire.) “I am glad,” he wrote to the Ojai (the local newspaper he himself had launched), “[the townspeople] care that my little school is to go on among their hills as it is because I do not know a better place for it … The best things in life don’t burn up.”

A few years on—1903, 1909—two more serious fires, yet no injuries, no buildings lost. In 1910, though, two days before Thanksgiving, there was no rebuffing the speed and appetite of a fire that had started downstairs from the Annex, one of the dorms. The fire was efficient and its toll was high: Study Hall, all classrooms, and living quarters for two classes, the Lower Uppers and the Upper Uppers. And the beloved Rough House. And, true to form, the next morning, despite insufficient insurance, another statement-amid-the-ashes from the founding headmaster: Rebuild again, and classes would go on. So would all of Mr. Thacher’s community involvement with and support of schools and newspapers and all sorts of other institutions in the Ojai Valley.

Not surprisingly, equanimity led to understatement in another missive from the east end of Nordhoff, California, to Watertown, Connecticut, educator to educator, friend to friend: A fire isn’t nice. Don’t try it. But we had no sense of anyone being in danger and hence no acute anxiety, though the fight to save the rest of the buildings was not without strenuousness and doubt for a while. I should be glad to have this cup pass from me, but it ain’t agoin’ to. So I’m going to get fun out of the rebuilding and making things better … The boys are fine, and I am sure are going to be the better for the experience…

June, 1917, the epic Matilija-Wheeler fire (the first of the three fires with “Wheeler” in their names), which began as an abandoned campsite fire and spread to take out many homes in the town. It did not harm Thacher, however, doing most of its damage in the narrow twisting canyon through which the Maricopa Highway now runs, and to the north and west of town. Another in 1929, and in 1932, the Matilija Fire, the 5th largest in state history.

September, 1948, at the end of a hot, parched summer, a hellacious heat wave and regrown slope sides made for another Wheeler fire, spectacularly large and damaging and begun when a butane heater at the up-canyon resort malfunctioned and set an oak tree and surrounding brush ablaze. But for the bravery and backfires of fire personnel, the use of large numbers of aircraft to ferry crews to the backcountry efficiently, and a salutary fog that rolled in after two days of burning, more of the Valley would have been lost. Again, Thacher was safely out of the crosshairs.

Other fires, many unheralded by news outlets other than local ones, dot the chronology between mid-century and July, 1985, the third of the Wheeler Gorge fires, this one roaring west to east, from the Maricopa Highway to the canyons north and west of campus in about 48 hours; it ended up lasting for over two weeks. Peter Robinson remembers: You could track its progress from the Pergola—a 4,000-foot fire line from the top of the ridge to the Valley floor. It settled in the hillside just at the back of the Upper Field, then leapt to the Outdoor Chapel, taking some pews with it, and around the back of the stables, lighting the hay barn on fire, . . . fall hay [having] just been loaded in the week before. The barn burned for three days. When we finally evacuated, I headed down the stairs of Olympus (I had been running the phones until it so got so hot that I knew I had to go) and saw flames in the Outdoor Chapel. Despite the presence of many, many firemen, I felt that the a substantial part of the campus would definitely burn. Yet all we lost, besides the damage to the Outdoor Chapel and the hay barn, was a student-built storage shed for lawnmowers located down near the baseball diamond. A couple of gas cans stored there helped that little conflagration along. Ironically, just before the fire made its leap, the automatic sprinkler system on the Upper Field turned on. … And a wind shift blew the fire back over itself.

December, 1999, the Ranch Fire. the result of two older teens setting off fireworks inside a mailbox in Sisar Canyon, Upper Ojai. Peter again: Fire crews put retardant on all of the houses that abutted the barranca. [What are presently] the Haggard, Perry and Halsey houses all sustained some slight burn damage. I remember standing below the old Huyler house [just below the Observatory] and watching the entire hillside on both sides of the barranca just glowing with embers. We evacuated the horses, which were in Carpenter Orchard, all but the last few crazy ones that could not be caught. The space was large enough for them to run around, and none of them were injured. Amazing night.

September, 2006, also human caused, the Day Fire, the largest California fire of the season and, from the ridge, another threat to the campus. Its wicked smoke set a Thacher campus evacuation in motion. Students were fetched in the main parking lot by generous past and present parents and alums and taken to their homes for most of the week, while much of the Mutau burned in the Sespe Wilderness of the Los Padres National Forest. Ash rained for many days, flakes of gray drifting down in the inevitable heat of that beginning-of-school month, and the backcountry landscape through which generations of Thacher horse and backpacking trips had trekked was rendered unrecognizable for several years, until the cycle of burn-and-regrowth was complete, chaparral showing its high capacity for bounce-back, seemingly dead oak trees coming back to life, even a species known as fire poppies asserting color and vibrancy on hillsides.

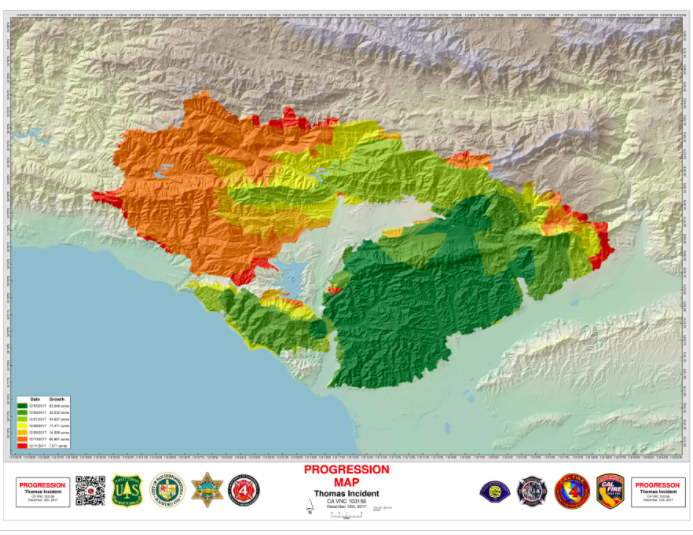

December 27, 2017 and still burning, though 89 percent contained, as of this writing, the Thomas Fire. Cause under investigation. 281,620 acres scorched, more than half of which is National Forest land. InciWeb reports “very little active heat at this time. No forward progress of the fire is expected at this point.” But earlier, fire behavior analyst Tim Chavez had outlined the conflagration’s size and scope: “This thing is 60 miles long and 40 miles wide. There’s a lot of fire out there.”

In every account I read, while water and hands-on-deck (professional, lay) were crucial, it all came down to the winds, always—how they shifted direction subtly or wholly, whether arriving as wicked Santa Anas or some other demon-breath contained in three words: Red Flag Warning. The alternative stories of calamity and favor are always implied in the ifs: “If the wind hadn’t changed …” “If the wind had only changed…” What one alumna wrote to me during the second week catches both sides of the lucky/unlucky coin with heartrending clarity: As the hours and days unfolded after our house burned to the ground, our eyes turned to the flaming ridge above our beloved school. To have also lost that most precious place, our compass in mind and heart—I don’t know. I don’t want to know. My gratitude to [the staff on campus], to the firefighters, to all the intricate behind-the-scenes working—is so boundlesly immense and deep. It feels like a miracle.

On the Wednesday night that the Thomas Fire seemed most intent on claiming The Thacher School, lock, stock, and barrel, the Incident Commander—or perhaps the Fire Chief (there were so many personnel safeguarding the front edge of the flames)—asked Michael Mulligan which buildings the crews should protect if the flames couldn’t be stopped at the campus perimeter. Michael told me the next morning, in the amazement of a campus still intact: “I knew the answer, but I didn’t feel ready to tell him. If push had come to shove, of course, I’d have said, ‘The Library.’ I didn’t want them going to their second option too soon.” (A local alumnus, CdeP 1968, had knocked at our front door the day before, twice, despite a veritable barricade at the gate: trucks, forest service and firefighters, Thacher work vehicles. “I want these guys to know how important it is to save the Archives. I need to know their plan.”)

On the Wednesday night that the Thomas Fire seemed most intent on claiming The Thacher School, lock, stock, and barrel, the Incident Commander—or perhaps the Fire Chief (there were so many personnel safeguarding the front edge of the flames)—asked Michael Mulligan which buildings the crews should protect if the flames couldn’t be stopped at the campus perimeter. Michael told me the next morning, in the amazement of a campus still intact: “I knew the answer, but I didn’t feel ready to tell him. If push had come to shove, of course, I’d have said, ‘The Library.’ I didn’t want them going to their second option too soon.” (A local alumnus, CdeP 1968, had knocked at our front door the day before, twice, despite a veritable barricade at the gate: trucks, forest service and firefighters, Thacher work vehicles. “I want these guys to know how important it is to save the Archives. I need to know their plan.”)

Yet shove seemed imminent at around 9pm, the flames moving as fast down the face of Twin Peaks as they had from Santa Paula’s Steckel Park that first night. “Looking at that wall of red and orange and pure white at its hottest, I thought, ‘OK, it’s likely we’re going to lose a large part of the campus.’ But almost in the next second, I thought, we’ve got legions of devoted alums and parents and friends, and we’ll rebuild. Mr. Thacher did. We can do it, too.”

In the end, a forty-minute wind-shift that began in a sort of quiet, held breath, allowed the firefighters, who’d been standing at the ready for a very long while after darkness fell, to set a long, assertive line of flame that was then lifted uphill, soon closing the gap between the torrent heading to the barns and this new, set fire. It was the end of the fuel at this vulnerable edge of the School. Friendship and the Annex, the Swans’ home, the hay barn, the Outdoor Chapel—and the entire campus south of that semi-circle—all saved from ruin.

Michael also had other thoughts, which he shared with me when I came into the house after my 10 hours away. “You know, I had this moment of acceptance last night, thinking how perfectly fire demonstrates the notion of impermanence. If you want to survive life, you have to accept that every phenomenological thing changes and is ultimately lost. That’s the way it goes. Everything we build and cherish that is not of the spirit expires.”

I, too, experienced a dagger of reality-awareness along these lines that terrifying night, a night perhaps made longer and more frightening because I couldn’t see the thing that, in all of its destructiveness, was also a force of awful and intense beauty. I tried to take my imagination beyond eradication to something positive on the other side of that portal. And if I played those mind games, then others must have, as well. In that acceptance of the possibility of only smoldering remains to the campus—even tried on as a garment not yet necessary but possible—lies the seed of shared commitment to the idea of a place, a school.

Unlike so many whose homes and lives were ravaged by this fire, we will not have to rebuild our house of stone (and others, of more flammable materials), and in that, these are the days of miracle and wonder, of grace and gratitude. I do not take them for granted.

Palimpsest in action: Lupine blooming along the Hurricane Deck during the spring following 2007’s massive Zaca Fire. Courtesy of Los Padres Forest Watch.

But if we had had to stand in ashes, I like to think—to believe—that the idea of Thacher would remain, however serendipitously planted so many years ago and then protected in its growing at every step, through every fire and flood, by that fine first headmaster and by those, down the decades, who loved the idea, or lived it, or both. Things of the spirit cannot burn.